Page 1 Page 2

It smells bad here. I don’t like it. It’s a clean smell like soap, but not nice. It feels sharp and bitter. It hits me like angry words. It burns my nose and stings my eyes when I breathe it in.

That’s the big smell. But there are others: dark smells stuck in the corners and the cracks where the big smell can’t reach them. They think they’re hiding, that no one can smell them any more. But I can. I know they’re there — the sick smells. Diarrhea and vomit and blood. Death smell. I smelled them hiding round Mama on her bed, around Madame Bopenda next door, and they’ve followed me here. Or maybe the smells came from here and found us. I don’t know.

I press my back against the wall and hug my knees to my chest. People dressed in funny clothes came to our house and brought Mama and me here. They frightened me. They looked like spirits wrapped in tissue paper. Mama was sick, and at first they watched me; they fretted over me like an old woman, thinking I might get sick, too. But I didn’t. And when I didn’t, they quit seeing me. I became invisible. I cried to see Mama, prayed to God, Baby Jesus and Virgin Mary to see her, but they wouldn’t let me. I didn’t know where she was. I asked everyone. Finally, a nurse told me she was in a place called Ward Two. I asked an old woman praying over her rosary, what this Ward Two place was. Her boney hand grabbed mine; the rosary beads bit into my hand. “It’s the dead place,” she said. “People go there to die.”

The other people who were waiting with me have left now, but their shadows have stayed behind. The shadow people weep and beat themselves against the wall. As they did when the doctors and nurses told them their loved one died. I see them. I hear them. Again and again and again. They follow me everywhere.

I watch a white woman speaking to Nurse Kulungu. Nurse Kulungu gave me fufu yesterday for lunch and some baked sweet potato. I know the white woman is one of the new doctors: one of the doctors not from Africa, but far, far away, farther even than Kinshasa. They are from America and France, Mama said.

Mama said their medicine was very powerful, more powerful than witches and bad spirits. When Mama heard they’d arrived, she was very happy. She hugged me and said it would be better, now that they were here. God, Baby Jésus, and the blessed Virgin had heard our prayers.

Meanwhile trucks rolled through our quarter with loud voices, telling us to stay calm, to stay in Kikwit, what to do, what not to do. In the markets people handed out papers. I took one I could not read. I saw pictures. I asked Mama what it said. She took it from me and told me not to worry. But I worried; everybody worried. The papers littered the ground like dead leaves. Soldiers blocked the roads in and out of town.

And the faraway doctors came, and what difference did it make to me?

Nurses and Doctors in the hospital have tried to get me to leave. “Your Mama is dead now. There are nice people who can take care of you,” they say.

But I don’t believe them, and when they try to take me, I kick and bite and scream ‘til they let me go and I run away and hide. I don’t want to believe them, because if I do then Mama is truly dead and never coming back. If I leave, then it is over. And I have not seen the body. I have not said goodbye. They leave me alone for now.

I study the white woman. She is tall and thin and pale. She makes me think of the cattle birds with their long bony legs and pale white feathers. Her hair is the color of sunshine and is pulled back behind her head like a tail. I don’t understand the words they speak. They talk and talk. My stomach makes noises. I close my eyes.

They told me a week ago Mama died. It was a week, wasn’t it? It seems like forever. Or maybe it was never. Maybe this is a dream. Yes, a dream and I will wake up soon.

I imagine Mama’s cool hand stroking my forehead, waking me from this nightmare. “Ça va, Christ, ça va; it’s all right,” she tells me. But the shadow people are wailing behind my eyes. I tell them to be quiet.

How many hours have I been sitting here? I wonder. Mama taught me to tell time. She said I was a big boy and old enough to know. But there is no clock on the wall with hands to show the minutes and hours. Only my gnawing belly tells me time is passing and reminds me I have not eaten this morning. Last night someone gave me kwanga wrapped in a banana leaf. I took it to my hiding place, unwrapped it from the leaf and ate it in tiny, tiny bites. I fell asleep praying to baby Jesus for a miracle.

I open my eyes, and the white woman is squatting in front of me.

* * *

I crouched down in front of the boy. “Mbóte na nge.” ‘Hello’ in Kituba and about the extent of my Kituban repertoire.

The boy opened his eyes and jumped to his feet.

“Ça va, ça va, it’s okay, I won’t hurt you,” I said in French. “Sit, sit.” I made a downwards tamping motion with my hands and sat down on the floor. I leaned my back against the wall and stretched my legs in front of me.

I looked up at him. I could see my reflection in his eyes. I patted the ground. “Have a seat.”

He hesitated, then slumped down beside me, all elbows and knees.

We sat side by side, neither talking. I could hear him sniffling. His stomach growled, poor kid. I reached over and took his hand. He didn’t pull away. The hospital breathed around us. Footsteps echoed in distant corridors, but no one passed were we sat.

The sniffles became sobs. Tears were streaming down his face, and I did what seemed the most natural thing. I scooted closer to him and pulled him into my lap. He weighed nothing at all, and I wondered when he’d eaten last. I rocked back and forth, my arms around his slight frame.

Wiry arms wrapped themselves around my neck. His body shook. “Shush, shush.” I murmured those universal comforting sounds that work in any language. Those mothering sounds all women instinctively know, even the childless ones like me.

Holding Christ in my arms, longing rose up inside of me — longing for home, for my own mother’s embrace, for a child of my own. Little fingers touched my cheek, and I looked down. Christ was looking up at me. I realized I was crying, too.

He asked me something in Kituba. In French, I told him I didn’t understand Kituba.

He gnawed his bottom lip, then tried again, this time in French. “Why are you crying?”

“Because I’m sad,” I said.

“Pourquoi?” he asked. “Why?”

“I am sad that your Mama is dead.”

“Ah… so am I.”

Time passed. The sun moved overhead to its peak.

He spoke and startled me, “Is Mama really dead?”

“Yes, Christ, she is.”

And five minutes later, “What is your name?”

I blinked. “Well, Christ, my name is Mary.”

He squirmed in my arms. I opened them and let him go. My lap was empty and cold with him gone. Standing in front of me, he extended his small hand. “Bonjour, Mary, je suis Christ.”

I shook his hand. “Bonjour, Christ.”

I scrambled to my feet. He slipped his hand in mine and looked up at me expectantly.

I squeezed his hand. “Okay kid, let’s go get you something to eat.”

Christ was hungry.

Page 1 Page 2

Pages: 1 2

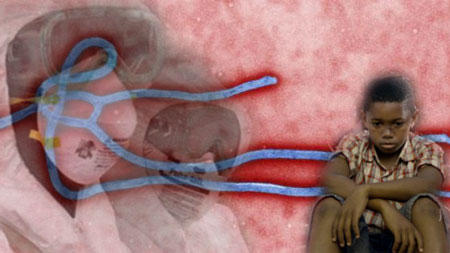

Congratulations Shani. I’ve enjoyed reading this version of it. A moving story and took me back to the period of the ebola epidemic in that country.

Love it and u are fantabulous at everything!!

Such a moving story. I really enjoyed reading it. I look forward to reading more from this author.

What a heart warming beautiful story about compassion in a time of desperate need, I thoroughly enjoyed reading this story and would love if it became a novel!