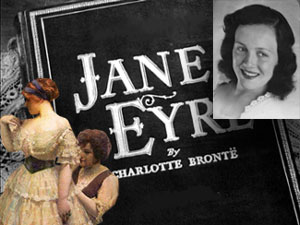

When my mom died, one of the things that nobody else wanted was a copy of Charlotte Bronte’s novel, Jane Eyre, that had been given to my grandmother when she was twelve. I had always been fascinated by my maternal grandmother, Alice, because my mom didn’t remember her much, and she looked so pretty in her wedding picture. My mom looked more like her father, who had huge laughing eyes and a long face. What prettiness she did have was inherited from that lovely, innocent bride who looked at us so sweetly from the sepia-toned wedding portrait.

Although her beauty was visible in the faces of her second-generation descendants, Alice never knew any of them. She had died when my mom, the youngest, was four. My grandfather married the sturdy housekeeper, Jenny, who became the only mother my own mother remembered — and resented. Her father, who she worshiped, died when she was 14, and she was left with step-mother Jenny, who dominated my mother’s life in ways that she never forgave. We were told all kinds of resentful stories about this woman.

It was something of a relief to me that this stocky old woman, whose house smelled like moth balls and whose opinionated ways seemed unkind to a shy, sensitive child, was not my real grandmother. When Mom told us the truth and showed us the wedding portrait, I began to fantasize about Alice. What was she like? Was she as sweet as she was pretty? What would have happened if she had lived? What would my mother have been like if pretty Alice, not sturdy Jenny, had raised her?

Then, I got the copy of Jane Eyre that had been inscribed and given to Alice as a Christmas present from a West Side Chicago church at the end of the 19th century. Alice had once held this book in her hands. Had she read it? What did she think of it? Had she loved this story as passionately as I did?

I remember doing a high-school book report on Jane Eyre but can’t recall if I was truly smitten with the story at that time. A college friend had given me a paperback version that had Charlotte Bronte’s portrait on the cover, and it was this copy I found myself re-reading over and over; certain scenes, that is. My all-time favorite was the garden scene where the seemingly unattainable Rochester comes to declare his love for Jane (after mercilessly wrenching a declaration of love out of her). For me, it was the ultimate romantic moment: impossible, unrequited love becomes attainable, and a hopeless dream becomes tangible.

But the main point of the book is not the realization of a passionate love that seems hopelessly unrequited. It is that Jane is able to maintain her personal integrity throughout the story: while being mistreated as a child (I never re-read that part), while being overlooked by Rochester’s rich visitors because of her lowly societal position, and while being tempted to deny her own basic morals in spite of her passionate love for Rochester. She even refuses a huge sum of inherited money when it would have made her a society woman, choosing rather to share her new wealth with the cousins she has come to love. Finally, she doesn’t deny her heart when tempted to sacrifice it to a cold, lifeless marriage. And she does all of this without anything or anyone to guide her except her own moral compass.

So, when I realized that Alice had held this very book in her hand (and had evidently kept it for years), I knew immediately that I had to have a daughter. Maybe it was because the possibility of Alice having been a kindred spirit suddenly left a gaping hole in my life; perhaps, unlike Jenny, I might have actually had something in common with my real grandmother. Maybe having my own daughter would somehow bridge this gap in my maternal ancestry. But perhaps the urge for a daughter came more from the sudden necessity to pass on a love for Jane Eyre. I felt as if Alice had left me something precious that I now needed to pass on down the female line. What can mothers bequeath to daughters? Beauty? China? Men can transmit the family name, but in four generations, we women have had four different surnames and my daughter’s will some day, most likely, be different than mine. What, besides dishes and genetic material, can we hand down? Stories. Our own stories: good, strong stories, not weak, resentful ones. Many different stories; stories like Jane Eyre, a plain heroine (the first of her kind) who overcame impossible odds, not because she was well-connected, rich or beautiful, but because she remained true to who she was.

When Abigail was born, we gave her the middle name of her great-great-grandmother Sophia, Alice’s mother, so that she could be reminded of her female lineage and, in a small way, bridge the gap that was left there by Alice’s premature death.

I’ve tried hard to expose her to the best stories, the ones that will help her develop into the woman she was meant to be. And at 15 years old, I’m very proud to say, she exhibits an amazingly voracious appetite for books. She didn’t particularly like the BBC version of Jane Eyre when she first saw it, but the compelling Toby Stephens version is what finally drove her to crack the book. She wasn’t disappointed.

Jane Eyre has, in a way, bridged a gap in our female line. And I’m very glad that it’s become a part of Abby’s life. Who knows what difficulties life will present her? Perhaps having the character of Jane Eyre in her mind and soul will help her to make those choices that will enable her to be her best and truest self.