|

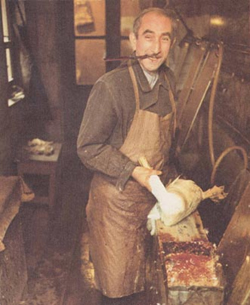

Nate's Fish and Poultry Shop

(continued)

By G. David Schwartz

My grandfather was a practicing Orthodox Jew. He taught me — more

than any teacher I can remember, more than any book I have studied since

— what it means to live in this world. He did not teach me the

Wisdom of the Fathers, nor the Bible and, while some might find this

absence cause for blame or censure, he taught me the more important

lessons in life — ones which cannot be obtained by any lesson or

any book. He witnessed the dishevelment of my mother's observance and

family with something less than a stoic attitude. He resolutely refused

to criticize my mother, at least while I was within hearing distance.

Yet his dignified demeanor assumed rather sad expressions when certain

topics were raised.

My grandfather kept kosher to the end of his life. When every bit of

his savings were depleted, he refused to abandon the "old ways."

Expense was never the issue. Although we lived in a city which was once

teeming with five or six dairy farmers, and a dozen kosher butchers,

it was a matter of dignity to maintain oneself, despite the fact that

there was only one butcher, and no dairy farmers. It was a matter of

dignity; not pride, not boastfulness, not arrogance. Dignity.

It would be very difficult to put into words all that my grandfather

taught me, for even though he has been dead these far too many years,

they are lessons I am still learning. Yet the word dignity seems to

encompass the virtues which best describe my grandfather.

He described to me once a teacher who, he said, "had it in for

me because I was a Jew." He described this teacher walking toward

him and leaning into his face to scold him. He described the crucifix

which hung from her neck. I don't recall how old I was when I heard

this story for the first time. In fact, among the repeated tales from

his life, this story seems only to have been told once, twice at most.

It was a terrifying story: being hated because of an "accident

of birth," for a particular approach to the divine. Yet at what

must have been the most terrifying part of the story, my grandfather

waved it away with the words that times have changed, are changing,

for the better.

Once, while my cousin Jerry and I were standing on a corner discussing

nothing in particular, a car of people seven or so years older than

our tender fourteen years asked us if we would like to have our "Jew

noses cut off." I don't remember responding. But I recall, in retrospect,

several times declining the offer. I do not want my nose cut off. I

do not want conditions which contribute to anyone even thinking I want

my nose cut off. And if I am committed to preserving my nose on my face,

then I am also committed to contributing to the change of circumstances

and change of environment which will preserve everyone's nose, everyone's

skin, everyone's life.

It is a matter of dignity; a matter of honoring the person who has taught

me most about prestige. The status which matters is not the reputation

we gain on our own. Human beings are convened in such a manner that

we really can do very little on our own. We are always standing on the

corner with cousins, or talking with beloved relatives, or working together,

or fighting together, or calling each other names together, or threatening

each other together.

Given the choice, I venture to guess that each of us would prefer to

engage in deep, genuine laughter rather than shared ridicule. It does

not take a whole lot of study or experiment to know that most people

would prefer sharing their time with beloved people rather than hateful

people. Nevertheless, we have a perceived social past which has been

bequeathed to us which we cannot simply put aside. It does seem to take

quite a bit of study, experimentation, and new experience to address

the litany of past wrongs the Jewish and Christian communities have

"shared" together. It would seem to require more and better

thought, developed toward more and better experience, to reconfigure

the now intimate, now horrendous relationship between the Jewish and

the African-American community.

We are always together. What we choose to do with our togetherness seems

largely to depend on the form we choose to arbitrate our relationships.

In some deep, abiding sense, the form which Jews and Christians choose

is the invisible form of the always impending relationships which occur

when people, two or more, ten or more, stand together. The form which

blacks and Jews have most readily available to choose from is the deep,

abiding pool of liberation which is redemption, salvation which is freedom.

We have not even reached the point where it makes sense to utter the

otherwise true, profound statement that freedom is freedom to pursue

rational, creative activity. We too often hold one another in bondsman

(and women) ship to our own prejudices; we are too often willing to

sacrifice the intelligence and skill of the other. Why would we want

to so mistreat ourselves? Why are we so little concerned to find our

dignity; the nobility which is to be had from working together once

we realize we are stuck together?

But in truth, even when I find someone who is a "polar opposite"

of me, a black person next to my white personage, a female next to my

maleness, a Christian next to my Jewishness, when we sunder the chains

which would bind us to the false idea that male and female, Jew and

non-Jew, white and black are opposites, we begin to sculpt a realm of

dignity and peace. We begin to see that we are not "stuck together"

but have an opportunity to make progress together and, indeed, are walking

together in one way or another, whether we care to affirm so or not.

When we begin to affirm one another, make one another visible first

to ourselves, and afterwards to our fellows, then we have the opportunity

to return not only to the genuine deep laughter of the love of life,

but of sincere joy.

|