|

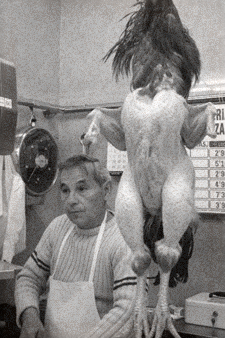

Nate's Fish and Poultry Shop

By G. David Schwartz

I do not particularly like eating chicken. This is a curious position

for a Jewish person to be in. Chicken is virtually the staple of Shabbat

dinners on Friday evenings. Chicken is the fundamental Jewish response

to illness. But I do not enjoy eating chicken.

Maybe my life would have been entirely different if the man I most

respected in life had not owned a chicken store. My grandfather, Nathan

Oscherwitz, was the son of a dairy farmer and milk deliverer. His father

was struck in the head with a pistol during a robbery attempt and died

some days later. My grandfather subsequently found himself investing

everything he had into a haberdashery. In later years, he liked to say

of this experience, "I lost the shirt off my back."

When I was born, my grandfather owned the poultry shop. My earliest

memories find me in that most unsanitary place, where live chickens

were butchered according to the specification of customers. I can see

images of my young self sticking my fingers into wire cages that held

between ten and thirty squawking chickens. I can hear my grandfather's

hurried warning not to stick my fingers in the cages as he turned from

one customer to another. "Okay, what do you want?" he would

inquire with a businesslike impatience.

I remember naming chickens, although I cannot recall any of the names

I gave the domestic fowl. Unbeknownst to me at the time, each of the

fowl was dead within hours or days at most. Nor did the twinkling look

of bemusement ever leave my grandfather's eyes as his gaze darted impatiently

from customers to tenderly observe me.

Spoiled, I was. I had the run of the store. I was in charge of naming

chickens and sticking my fingers into cages where, yes, they were pecked.

But in retrospect, it is not clear who ran the store.

Clearly, my grandfather was the owner. But when I reach into that bemused

perspective that my grandfather willed to me even while he was alive,

it is apparent that the chickens ran the shop. They cackled when anyone

approached, and everyone present knew that the cackling was a demand

to be left alone, or taken. Once in awhile one of the men would reach

for a chicken and, in response to the cackling which was delivered,

either leave that particular chicken alone, or speak with it as it was

taken behind the counter, behind the great wall, to be slaughtered.

My grandfather, the men who worked with him, myself, and the customers:

we were all at the bidding of the chickens. And I suspect that my grandfather

and the men he worked with knew it.

There was a symbiosis between myself and the chickens, between the chickens

and the shop, and between the men who worked with my grandfather and

the job which had to be done. They were great black men, as any man

is great to a child who stood only four foot tall. They had great, guttural

laughter and I, the prince of chicken naming, was also the crown prince

of generating laughter.

The issue can be raised: were these men genuinely happy? Was it just

my impression or were they engaging in a denial of their true feelings,

a show which would have been their perceived qualifications for keeping

their job? It is a matter of honoring my grandfather to at least think

that I experienced his intimacy with these men, their freedom to be

genuinely at ease in the shop. But does remembering in this manner simply

mask the truth?

My grandfather would have restrained no one. The proof? Smiling black

men — Jake, Bert, Mo — would take time from their activities

to stand next to me, put massive arms around my shoulders, and ask in

a teasingly astute manner: "How do you know that one's name is

Henry?"

I was never "Dave." I was always "Nate's grandson."

For someone who had always been told "David! Get away from there!"

or "Don't do that, David!" the change was refreshing.

Later, a friend from South Carolina would tell me that at the very same

time in her life, black men would not dare address a white person by

their first name.

What a rush! In the world controlled and directed by the life, naming,

and death of chickens, my grandfather was "Nate," and I was

"Nate's grandson."

How different are our experiences.

|