|

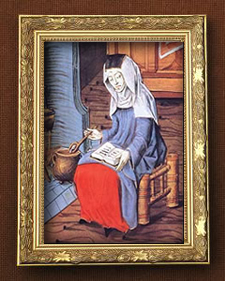

Me and Margery KempeBy K.A. Laity Margery Kempe was a woman who lived in the Fifteenth Century and had

visions of Jesus. People thought she was a bit odd, even though revelations

of that sort were considered to be a good thing on the whole. This all

got started after the birth of her first child, when she fell into a

mood of violent despair. We might call that postpartum depression now,

but at the time folks considered her to be beset by demons. Margery

was abusive to everyone, including herself. She bit her own hand so

hard that the scar remained for the rest of her life. After about six

months of this, Jesus suddenly appeared, sitting on the edge of her

bed and looking like a hero from a medieval romance. Holy figures usually

appeared well-dressed in sumptuous fabrics and smelling like flowers,

but Margery adds that he was also very handsome. He talks to her like

a BFF, asking why she's abandoned him when he never abandoned her. The

next thing you know, Margery is up and about, back to her old self once

more. I have never had a vision of Jesus appear to me. When I think of Jesus,

the first image that invariably pops into my mind (despite all my years

as a medieval scholar) is the way he appears in the SCTV version of

the epic film Ben Hur. As in the Chuck Heston film on which it's

based, their version features Jesus by metonymy, as if his divinity

is too much even for Cinemascope: we only see an arm. For SCTV, the

arm looks like it belongs to some wise guy, heavy with tacky jewelry.

Not being a Christian, I suppose it's not strange that a) I don't imagine

Jesus in an orthodox way or b) I haven't had a vision of him. I did

have a vision of Kurt Vonnegut, though. He was still alive at the time,

so I don't know if it counts in the same way. Perhaps his body was slumped

over in a chair somewhere while he was astrally projecting into my consciousness.

He did have a kind of halo, and he did offer comforting words like Margery's

Jesus (something along the lines of "Hey, kid, don't worry too

much, things are going to be okay") which seemed thoughtful if

a bit vague. He, too, sat on the edge of my bed, but rather than the

relaxed hero that Margery saw, I sensed that Vonnegut was a little uncomfortable,

as if this was a kind of duty call owed to an ailing relative. I didn't

want to take advantage of the situation and quiz him about various choices

he had made over the years in his novels. It just didn't seem right,

but looking back I wonder if I could have made better use of the opportunity.

So it goes. It's always hard teaching Margery to my students, because they tend

to react to the woman just as her contemporaries did, with irritation

and impatience. The first Jesus incident was not the last. The guy turned

her life upside down. Before she made him her full-time occupation,

she tried other things — brewing and milling. The beer went flat,

and the horses wouldn't tug the mill around. Margery's businesses failed.

She finally figured out that Jesus was the only way. Margery would see Jesus everywhere; not like Waldo, more like that

Trystero symbol in Pynchon's The Crying of Lot 49. Once you know

to look for it, it seems to be everywhere. Whenever Margery saw Jesus,

she wailed and cried. This was often because she pictured him at the

crucifixion. Think Mel Gibson. For late medieval meditation, it was

all about the gore, the pain, the suffering: a practice that was called

"affective piety." Here is a man in pain; how does that affect

you? He's in pain because of you; how does that affect you? For Margery

it brought out instantaneous bawling at full volume. She wept and wailed

and moaned so much that fellow pilgrims on the road to Jerusalem abandoned

her. One of them told her, "I wish you were in a boat at the bottom

of the ocean." My students often wish the same thing. They seem to resent that Margery tried to have it all: husband and Jesus, family and holiness, sex and virginity (or at least chastity). She didn't want to stay within the confines of the church, however. Margery visited the anchoress, Julian of Norwich, but she didn't stay,

and had no intention of being walled up in the side of the church like

that: she wanted to travel around, to share the good word and her visions.

Some people had doubts about her visions, though. In the Middle Ages,

there were believed to be three kinds of visions: divine, demonic and

human. Guess which one matters least? That's right, the human kind.

Demons might at least sprinkle their lies with truth, but human visions

were nothing but folly. Attitudes aren't much different now. Who matters

less than writers? Isn't that what the length of the Hollywood strike

conveyed? My students tell me that anyone can be a writer now —

blogs are the great equalizer — so nothing romantic clings to the

word. Only someone with access to the divine might actually hit the

market hard enough to make a million little pieces. As a writer, though, I must admit to feeling more aligned to the demonic. After all, what is writing but the skillful telling of lies? I don't mean in a cynical James Frey/Margaret B. Jones kind of way. Or maybe I do: our lies have to feel more real than the truth. The truth is messy and often stretches the bounds of believability. There's a reason we have that saying, "truth is stranger than

fiction": fiction makes sense. Who can remember the truth anyway?

Margery at least had Jesus popping up now and then to keep her honest,

but she didn't have her story written down until twenty years later.

Even Jesus might have found it hard to recall everything with divine

precision. Those of us without a divine mentor must rely on more dubious

muses to guide our narratives. Who's to say what's right, what's true?

Editors, peers, readers? It's hard to say. I just hope that Vonnegut

is watching me from somewhere beyond the veil. With luck, he's not shaking

his head. So far I haven't bitten my own hand — maybe that's enough.

|