Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 Page 5

Woolworths at Cedarbrook Mall, just outside my home town of Philadelphia, didn’t look like much, but that was beside the point.

Back in the Sixties, it was a great place for teenagers like me to visit during trips to the mall, especially the variety store’s record cut-out bin. Filled with carelessly tossed-in crap, near-crap, and the occasional gem, at 33 cents for a 45-rpm single, a buck for an LP, it invited those long on musical thirst and short on cash to find keys to their universe.

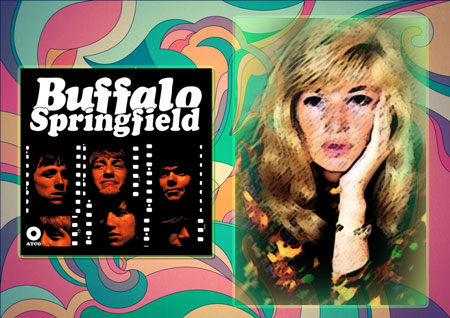

One afternoon in 1968, I found one of mine, a rare version of Buffalo Springfield’s self-titled 1966 debut LP. Overflowing with clever, hook-filled songs, minus the one tune most people ever heard by the band, it starred three hyper-talented guys who went on to bigger things than cut-out bins: Richie Furay, who fronted the influential country-rockers, Poco (the cartoonist behind Pogo wouldn’t let them use the name), along with Steve Stills and Neil Young. They went on to be, well, Steve Stills and Neil Young.

And while it was Young who penned two of the LP’s most memorable numbers—an ode to alienation with the confusing title of “Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing,” and a tune about a guy who loses his girl because he smokes pot, appropriately called “Flying on the Ground is Wrong“—Stills wrote and sang “For What It’s Worth.” That was an enduring protest song, capital P and S, which sold well as a single, and which the record company added to later pressings of the LP. My cut-rate beauty was a first edition that languished in the store after the change was made.

That move made sense for the company, and certainly for Stills, but I didn’t know or care much about it at the time. For a buck, I got the LP, which I played to death for months, long before I learned that, as a collector’s item, it was worth more because it lacked “For What It’s Worth.”

And when I finally realized what I had and announced it to classmates at lunch at Temple University, my way-too-loud voice carried to an adjacent table and caught the ear of an attractive blonde named Gretchen, who ambled over, introduced herself, and confronted me with two offers she thought I couldn’t refuse.

“Buffalo Springfield without ‘For What It’s Worth‘? I gotta have it. Bring it in tomorrow, and if you’re telling the truth, fifty bucks.” (Righteous bread in ’68.)

Trouble was, she was standing, I was sitting, and try though my eyes did to reach her face, they lingered on the rest of her, too. (Shit, I was 17.) I think she noticed, because when I turned her down, she upped the ante.

“OK, OK. How about this… you bring in the record, and I’ll sleep with you.”

She didn’t actually say “sleep with”—something far coarser—but you get the idea. Except I was a bashful virgin at the time and really didn’t get the idea; I muttered “nah,” perplexing the guys at the table and sending Gretchen back to hers. She looked wonderful walking away.

“What is wrong with you, man?” lamented several of my fellow long-hairs. “Ah, come on,” I sputtered. “She would’ve taken the album and left me hanging. I don’t even know her.”

That changed, eventually, though it took seven years, by which time I was neither bashful nor a virgin, and, so I thought, no longer intimidated by forceful, free-thinking blondes.

One May Sunday night in 1975, I was leaving my parents’ West Oak Lane house, on the way to my Baby-Boomer-issued VW bug, which would lead me to my Germantown apartment, when Gretchen appeared in the gloaming, walking a large dog.

I feigned car-key fumbling until they reached my parking spot, then offered a hearty “Remember me?”

“You didn’t want my money and you didn’t want my body. You’re an idiot.”

“Yeah, well, I wasn’t quite ready for all that then.” Her dog—-she called him Dandy—put his front paws on my cut-off bare knees. “I wouldn’t have been much in the sack.”

She flashed a wicked smile. “Probably still aren’t.”

I wasn’t sure where to go with that, so I let Dandy step up to the plate. I took his front paws in my hands, looked deeply into his eyes in the fading light of dusk, and warbled the opening line of, you guessed it, “For What It’s Worth.”

There’s something happening here, what it is ain’t exactly clear

“You still can’t look me in the eye, can you, Stuart? That’s the name, right?”

I admitted as much, spewing out, kind of all at once, that after graduation I became a newspaper reporter, had a live-in girlfriend for a few years, no more, and I still had the LP, in a frame on my wall, no less.

“Well, I don’t want the album anymore, and I don’t care about your love life, in case you’re brandishing your single-hood as some kind of treasure I’m supposed to mine. Not interested.”

Except she was: By the time Dandy made it clear he’d had enough of our chitter-chatter, she’d scribbled her phone number on my right wrist with a Bic.

(continued on page 2)