|

The Red-Headed StepchildOn the landing between the first and second floor, John points out the million-dollar stained glass saint, the Saint of White Elephants and Wallets. On the second floor landing, he shows me the two-million-dollar wall-sized portrait of George Washington, the endless rooms with seating for a thousand on Easter morning, the cigar room, library, business center, bars, of course, and then tells me about the rooms upstairs: the nap room for the eighty-year-olds, an ancient fire escape for the hookers who would sneak in during the Fifties leading to the now-empty third floor. We end up in a portrait-covered room, the eyes of presidents no one in my family ever voted for, except for Nixon, the terrible mistake of my grandfather, who quit running the Democratic Party in Huntingdon forever after. He'd sold apples in a pushcart, then insurance through the dust of unswept streets, left this legacy of labor and service and unwealth. I hadn't thought about my grandfather in a long time, or what he might have had to do with my being a teacher and making nothing, until those old presidents surrounded me, an ambush, like the faces on money. John latched onto me in high school, an unrecognizable time ago. John's genes came here on the Mayflower, and here, in his Center City hideaway, he occupies the seat father after father has settled in and then vacated. John's full of rants. John moves easily among the leather chairs, the men sunk into them or propped up by them. John's going off on how the world's gone to hell faster than the rats out of this school building John just demolished — and now the Philadelphia's chock full of people (like me), who haven't cracked the code, are not on the team; the clueless masses. He glides to the next group of men holding onto drinks. He's talking about Palm Springs, the moonscape golf course and the dirt they had to carry in for the fairways. He's talking about trailers stacked atop each other New York style, the outer curtain of the new Comcast Center, 9/11 fire escapes, and millions lost on an airport project. John's drinking Wild Turkey straight up like it's ginger ale. How jealous I am, green as a three-dollar bill, wanting for myself the ease of his patter, the world he's not only insinuated himself into but asserted and defined himself by. He's large, made of thick, hearty stock. It's okay that John's showing off what he's made of himself. I've got ex-students, grown-up and sending me e-mails from college and beyond to let me know I've helped them. A little.

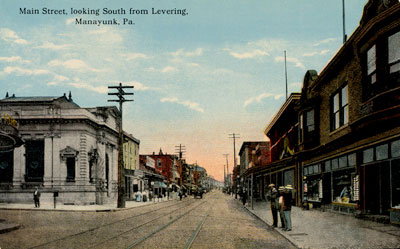

The thing is I don't deserve such a place. The thing is that's what such places remind me of, my dust-covered grandfather, pushing his cart like Sisyphus, an absurd task, until he became the task itself, turned to dust. And so what? Imagine a rest stop on the way. A place such as here, for people unlike me. "You look like someone who's had a tough paper route in Manayunk," John stops to say to me, Manayunk a part of Philadelphia with tremendous hills, and then he's off about what a dickwad the mayoral candidate is. No shit? the vice-president of some bank says. John's the answer man, and I'm empty of words. Does Howdy Doody have a pair of wooden ones? John's talk has the bombast of the past, not the yawp of Whitman, but the whoop of war. Yessiree. John now and then remembers me, introduces me as the guest. Everyone is nice as could be. Everyone says welcome to the league. Everyone wants to help me in any way. Just name it. Oh, what could I say? Give some working-class prideful bullshit line about how we were too busy pushing our rocks up a hill for some coin to learn tennis, golf; too exhausted to bandy about lines and come up with anything to say except, "Fuckin' job." I worked in my father's factory through college, picking out tiny parts to send all over the world. Give me another past. "Hey, this guy fly-fishes," John says to an old man who just had triplets. John grabs me and tosses me into the guy's way. We talk fly fishing, and he invites me to his club. "Won't cost me a thing," he says. Cost him eighty-nine thousand in upfront money. "I've only got backyard money," I tell him, not knowing what the hell I'm saying. I'm not drinking, an attempt to fend off an impressive history of alcoholism, all the way back to Ulysses S. Grant, Jesse James; a strange, gnarled line my grandfather once traced, all the way back to Adam and Eve and some incestual beginning. Then John's dragging me away to the concert, telling me I'm like the red-headed stepchild, apologizing for my discomfort. I don't shake it off. It's real and it sticks. John puts his arm around me and says I'd feel just as out of place at a gathering for cross-dressers and leather fetishists. "Don't be so sure," I tell him. "You nasty," he says. John slips something into my palm, not the pills we used to swallow

but a ticket now. We're seeing Roger Waters. Back in '79, we saw Pink

Floyd in Madison Square Garden when they built a wall, fucked-up out

of our minds on pot John grew in a closet and shrooms bought from a

policeman who stopped us a mile away from the stadium. The world dissolved,

boundaries blurring and smearing until no one had a face and I lost

my self and thought I'd never get it back. Sometime in the midst of

it, John hugged me tight. "The music, the music, they know,"

he said and I think I cried into his barrel chest. "Yes, definitely." |