You had some fun with this idea with one of your shorts, Asian

Pride Porn. And it turned out to be about the role of humor in developing

a mutual understanding of some societal issue.

Asian Pride Porn is the most polemic thing I've ever done, because basically Asian Pride Porn is about challenging the emasculation of the Asian male in American media. But it's done totally tongue in cheek. And yes, I think humor is a great way to get these ideas talked about, you know?

I did Asian Pride Porn with the Internet in mind. When people first started to put movies online, I was like, "I'm just going to make a movie to put online. It starts with 'A' so it's at the top of the list. It should have the word 'porn' in it. And it should be three minutes or less, because that's people's attention span."

And you've getting both people who are just looking to non-ironically consume Asian porn and end up finding "Asian Pride Porn." And a lot of them are amused by it. It cracks them up, and it makes them think about what they're consuming otherwise.

And I guess that's one of the most popular films at AtomFilms.com.

Yes. There's another short film I've got at Atom Films called All Amateur Ecstasy. That film just keeps going. I mean, it's crazy. In terms of percentages, in terms of budget to profit ratio, I think that's the most profitable film I ever made. Because I think the budget on that was maybe $200, and it's a couple thousand.

In addition to humor and science fiction, you've also done a documentary, Fighting Grandpa. Why was it important for you to explore the relationship that your grandparents had?

My grandfather, his death had a big impact on my family. And I think when he passed away, I just saw my father struggling with the death of his father. And I saw my father as a son. And it was a pretty big experience for me. And there's a way in which my dad's and his siblings really had a lot of difficulties with their father. It was a really compelling story to me. And it was something that I needed to figure out for myself and try to understand.

I started making that film because I wanted to try to understand who my grandfather was. And during the course of making it, I was like, "I'm never really going to know." That there were so many different interpretations. Everybody in the family had a different take on that. And eventually, the film really became about my grandparents, about my grandmother and eventually, whether my grandparents really loved each other, which is a pretty hard question to ask.

Actually, I think there's a theme that came out of Fighting Grandpa, that related to a lot of my stuff, including Robot Stories, which is this notion of this struggle to communicate. That we aren't always good at articulating what it is that we're feeling. And that love can be expressed in many different ways, and sometimes we miss those expressions and sometimes we catch them. But it's the struggle to try to figure out what language people are speaking.

So you went from something that was very personal to something that's universal.

Well, yes, I think that's the way it always works. I mean, this is a Spike Lee thing. The more specific something is, the more universal it can become. That if you're really, really true to any little moment, no matter how small it is or how weird or specific it is, if you really get to the heart of what that moment is about, everybody can understand it.

In a similar kind of way, Fighting Grandpa was a very specific film about this very specific Korean-American family, which is different from everybody else. It's a unique experience. But at the same time, it's everybody's experience. Because particularly in America, so many families are immigrant families. There would be this struggle to communicate across generations. I've had Jamaican people come up to me and say, "Those are my parents. That's my grandpa." I've had people from England come up and say the same thing. And I think that's the real glory of filmmaking, is that it's such a visceral sort of medium that it can create these experiences that everybody can tap into.

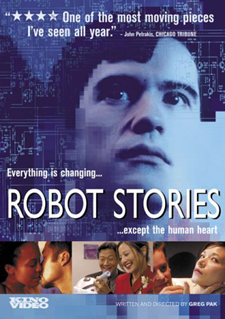

It's the same thing with Robot Stories. Robot Stories has got this primarily Asian-American cast, and it's played all around the world. It's won audience award in places like Spain.

Was it a conscious choice to use primarily Asian-American actors in

Robot Stories? And if so, why did you make that choice?

I'm mixed race; I'm half Korean and half white. And when I was writing the stories, I pretty much saw them in my head the way you saw them on screen. I saw these characters this way. Like, for example, the second story, the relationship between the mother and the daughter. To me that's just so typically this Asian-American thing. The way they communicate or don't communicate, the way the mother lashes out at the daughter, the way she won't talk about certain things. The way the daughter kind of doesn't push her all the way to talk about certain things. Those things come out of my own specific Asian-American experience. But because they're true, everybody gets it.

A few of these actors have been in some major Hollywood films. How did you end up working with them? What was your casting process like?

I think the best known actors up there are Tamlyn Tomita, who plays the mother in the first story. She was in the Joy Luck Club. She's certainly a well-known actress. She plays the lovely and stalwart scientist in The Day After Tomorrow. The very tentative love interest. She was also in the pilot of Babylon 5.

Sab Shimono, who played the old sculptor in the last story — he hates when I say this, but I always say it — he was the village ogre in Waterworld. He was also in a sci fi movie called Suture. And he was the voice of Mr. Sparkle in The Simpsons.

And then a stealth famous person in our movie is James Saito, who plays the father of the robot baby. James played Shredder in Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. You'd never know, because he was wearing a mask the whole time.

So a number of these actors are folks that I've gotten to know over the years, like Tamlyn I've gotten to know over the years at different Asian-American film festivals. And I made some shorts before I did Robot Stories; I'd go to these film festivals, and in Southern California, Tamlyn would go to these film festivals. She supported them. And she's really down with independent filmmakers and supportive. And she'd go to the shorts program, which is unheard of. She was one of the most famous Asian-American actors out there, just chilling on a Saturday afternoon watching shorts. And so I got to know her through the festivals and eventually, when it came time to make my feature, I asked if she'd do it, and it all worked out.

My producer, Kim Ima, is also an actor, and she had done a play reading with Sab. And that was the hardest role to cast, because we needed an Asian-American leading man in his 60s, someone who had this kind of presence, like an Asian-American Clint Eastwood or somebody like that. Or Tommy Lee Jones. Somebody who had a kind of sexual presence, to be honest, to put it directly. Somebody who had a kind of earthiness and leading man quality. And there's just a handful of actors out there who fit that bill. And we got the best one. And Sab was just tremendous.

Other folks were folks I'd worked with in New York on different things. Vin Knight is a very good friend of mine. And I did improv comedy with him for years and years. And I tapped him in a couple little roles. He's the guy in the elevator who kind of gives me a funny look when I get off of the elevator. Some folks were just folks I knew and knew would be perfect in some small roles.

Everybody except Tamlyn and Sab were actors in New York. And a lot

of them were people I worked with over the years. Other folks were folks

that we brought in and auditioned.