|

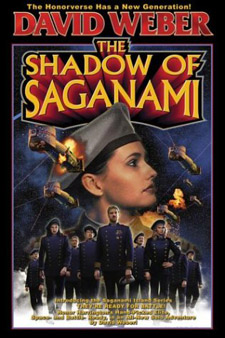

David Weber(continued) Interview by Alyce Wilson What's your writing process like on an individual project? Well, I sit down in front of the computer, and I talk to it. I did want to ask you about that. You said you use a voice activated software. Do you dictate all your writing? Yes. I use Dragon NaturallySpeaking. And basically, it's simply a way of getting the characters onto the screen by talking to it. It's better than keyboarding it. There are both strengths and weaknesses, advantages and drawbacks to it over keyboarding. The decisive advantage for me is the advantage to my wrist and my hand. I can't type for extended periods, and this lets me continue to work. And to have the text in front of you immediately, right? Rather than having somebody transcribe it? I couldn't work that way. I have to be able to edit as I go along. Otherwise, there's no point. When I'm in the groove and really engaged with a book, and I'm pushing closer to the deadline, I work 10 to 14 hours a day. And I'll produce between 5,000 and 10,000 words a day. Probably have to spend a half day or so worth of time editing of that 10,000 words. But I would say that I probably average 5,000 to 7,000 words a day when I'm really coming down the groove on a book. Other times, I may only get 1,500 or 2,000 words a day. And especially when the book is just starting to come together in my head, there are frequently days when I don't get anything written, because I'm doing other errands or whatever. It's still cooking around in the back of my head, heading towards what I ultimately end up putting on paper. How much do you outline or sketch things out ahead of time? As far as individual stories is concerned, if it's a solo book, not a great deal. I do a lot of background notes. I do a lot of character development, establishing the toolboxes for my characters where I put, like, technological advantages and limitations. I know how I want the book to begin. I know how I want the book to end. I add a couple of way points along the way that I want to reach. But, by and large, when I start writing the book, that's pretty much it. Collaborations are different. Collaborations, you need a shared road map if you're going to get to the same point. And I've got a little bit of that going on in some of my solo stuff now because of the effort I'm making to weave The Crown of Slaves (2003) and Shadow of Saganami (2004) story lines in and out of the main stem Honor books, so that I'm finding myself doing a lot more in the way of outlining the secondary books before I ever begin on them, so that I can be sure that I get everything I need to get done in them done. What brought you to writing? Why did you start? I don't know. I started writing in fifth grade, and it's just something I've always done. I was supporting myself full-time by my writing and typesetting and whatnot by the time I was 17. And I've supported myself by writing or associated stuff, with the exception of one summer that I spent working for Tweetsie Railroad in Maggie Valley, North Carolina, as a blacksmith. Well, also I spent one year working in a textile transfer printing plant while my wife, my first wife, finished her undergraduate degree before we headed on up to Boone, North Carolina, for me to do my graduate work. But I just don't remember a time when I wasn't putting words on paper. People ask me how [I] learned to write. And my response is to ask them how they learned to walk, because that's how you learn to write. You do it. And you throw a lot of it away. Just like babies fall down a lot learning to walk. Would you consider yourself self-taught? No one can teach you to be a storyteller. They can teach you how to do it better. You've got to have that inborn need, urge, whatever, to tell stories in the first place. You have to have that sense of this is how a story is communicated. Then you can work on refining that. That's where someone can step in and teach. But they can't make that first step for you. You've got to take that one on your own. That's the bad news. The good news is that I think more people have that inherent capability than realize they do. And you have to also have the confidence to risk failing. I could have been published ten years earlier than I was, if I'd been willing to go ahead and take the chance. But it's a very hard thing if it's something that you really, really want to do. A lot of people fail when they try to do it. There's this great temptation to always be the fellow who's almost finished with his book, the one who says he's going to sit down and write, because as long as you haven't been rejected, you haven't failed. And as long as you haven't failed, the dream is still there. And then you look back and you realize "some day's" come and gone, and you never risked failure, and it's now too late to succeed. What authors have inspired you? Every author you've ever read inspires you one way or another, influences you one way or another. [Sometimes], it's like, "Well, that's something to stay away from." Every writer stands on the work of every writer before him. Even writers that he has not read himself. If you are a fantasy writer today, you may never actually have read any of the Conan stories yourself. I guarantee that one of the people whose writing of fantasy inspired you to be a fantasy writer has. And so there's an echo of Conan, or Bran Mak Morn or one of [Robert E.] Howard's other characters in your work, even if you don't know it. But there are specific writers whose work I greatly enjoyed when I was younger, and I certainly see echoes of it in my own. I would count Keith Laumer, H. Beam Piper, Robert Heinlein, [Roger] Zelazny, although to be honest, Roger and my styles are sufficiently different that it's more... He was also a researcher, somebody who wrote from a broad knowledge base, specifically his use of mythology. Yes, yes. Roger was definitely a scholar. And it showed in his work.

He was more into the history of literature and myth than I am. I'm more

into military and diplomatic history. But there's a cross point in all

of that, a cross-pollination.

|