|

|

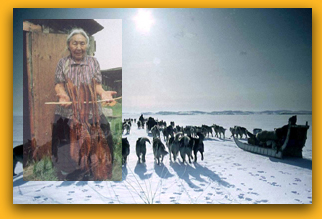

Inuit

Culture and |

|

It was quite obvious what the Europeans were attempting to accomplish when they married a native woman. Their motive was to spread European culture, beliefs, religion and capitalism (make money), and in order to do this, they needed to build themselves a family. According to Bruce Cox, who wrote Native People, Native Lands, the Inuit and European ethnic identities did not completely fuse together, because of their differences of culture and customs. I agree with this, because I feel Peter's wife did experience both continuity and change, in the face of racial intermarriage. Before the white man came, her life consisted of Inuit families helping one another, whether it be hunting, trapping, skinning the animals for food or preparing the meat and fat. They would gladly share what little they had with someone who was running out of something (Peter Kulchyski, Don McCaskill and David Newhouse, 1999). Yes, there was much sharing of hunting techniques, hunting lands and occasionally mutual aid, a sense both of similarity and of difference of shared ways and contrasting ways. Yet, when the Europeans arrived, Inuit families were faced with Anglican religion and new customs, dictating different family structures, division of labour, economic control and distribution within the family and settlements. This was quite different from what she was accustomed to when families did not live separately. On the other side of the coin, some native women under the leadership and authority of an Inuit extended family, in my opinion, were exploited and abused in the hands of either the father or husband. The native women under group leadership were subject to penalties that could be imposed by leaders in authority. If a woman objected to her husband or father's decision, she would occasionally run away. The situation may resolve without dispute or it may result in severe physical abuse (Garth Taylor, 1974). Either way, I feel women lacked somewhat in support and self identity. If Peter's wife did not agree with his decision making, she may have felt bound to obey anyway, both because of her ideas of familial authority and because she might have faced prejudice or racial discrimination within the English settlements, preventing her from seeking outside support. It's probable she felt confined and intimidated at times, taken advantage of in order to fit in and be accepted in the white man's society. Another problem she may have encountered, being as young as she probably was, were diseases like smallpox or measles that came from Europe, threatening her health and her life. Against these ailments, she could not depend on her native skills for survival. Epidemics of European infections caused far more severe symptoms and mortality among the natives in North America, due to their low immunity system (Labrador Inuit Association, 1977). Therefore, I believe Peter's wife had a hard life and was afraid of her new role model of either being a wife, living in a strange family environment and then becoming pregnant. As far as I have been able to establish, they had a daughter named Marie Louise Leon, who later married Tom Maurice, an Anglican man. Now, whether Peter's wife remained in St. Augustin (once owned by the Innuit) or not is not known, because generally Inuit and Innu were not exactly neighbourly. They were two distinct groups of native peoples in Labrador. According to the white settler, the Algonkin speaking Innu were formerly known as the Montagnais/Naskapi and identified as "Indians," and the Inuit who spoke Inuktituk were known as "true men," formerly called Eskimos. So my question is, how did she survive in an Innu community? Oral tradition suggests that the Innu and the Inuit were merciless enemies, continually at war. Before the 1300's, the Innu were the sole occupants of the Labrador coast until the Thule Inuit migrated from the north. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Inuit expanded south, pushing back the Innu and restricting their access to coastal resources. At this point no evidence of Innu-Inuit warfare has been found. Also, the Innu were exposed to the Jesuit Relations who thought they were religiously deficient, according to the journal Montagnais Missionization In Early New France: The Syncritic Imperative, written by Kenneth M. Morrison. The Jesuit teachings demanded conversion to the Catholic faith, without any real understanding of the culture of the Innu. The Innu were the first to come in contact with the Europeans, in particularly with the French. They were the ones who developed commercial, political and military alliances with the French but soon found themselves commercially displaced and politically subordinate to the French and harassed by the Iroquoian after 1633. As a result of the French take-over and then the British by 1713 (Treaty of Utrecht) and then again by the French, according to Canada's First Nation, written by Olive Dickason, cultural misunderstandings led to unintended insults. The Treaty of Paris, signed on Feb. 10, 1763, brought a long-waged war between the English and the French to an end. Consequently, under the terms of the treaty, the islands of Miquilon and St. Pierre were ceded to France. Therefore, France maintained the right to fish along a portion of the Newfoundland coast, while all the other lands were given to Britain.

|

|